Mother, you are not just my mother.

I know we fight because we love

I immigrated to the United States in the late nineties, though the story really began earlier. My grandmother sent my mother ahead first, hoping America might offer her a second life. In the meantime, my grandmother raised me herself. This arrangement explains many things, including why my mother and I love each other fiercely yet rarely gently. When she says, “You’re just like your grandmother,” it arrives without warning, interchangeable as praise or indictment. I’ve learned not to ask which.

Publicly, I’m effusive about my love for my mother. Privately, we argue far more than we exchange explicit tenderness. Somewhere along the way, we reached a quiet détente: we fight because we love. After her divorce, and once I could finally make ends meet, Christmas stopped meaning home. Home had grown too quiet, too honest about the fact that it was just the two of us. So I began taking her elsewhere. Vegas, for food and spectacle. Beach resorts, for memory-making and sunlit distractions. Anywhere that wasn’t a living room quietly missing people.

This year is the first time I’m taking her abroad. I considered Japan, where I’ve been living, but logistics intervened. More truthfully, I knew she’d been avoiding the place she was born. So I chose Taipei. I booked late, during peak season, and ended up finding an Airbnb in Ximending, where we lived when I was little. We’ll visit my grandfather. I know she’s missed him, though in our culture that sort of thing is rarely said aloud.

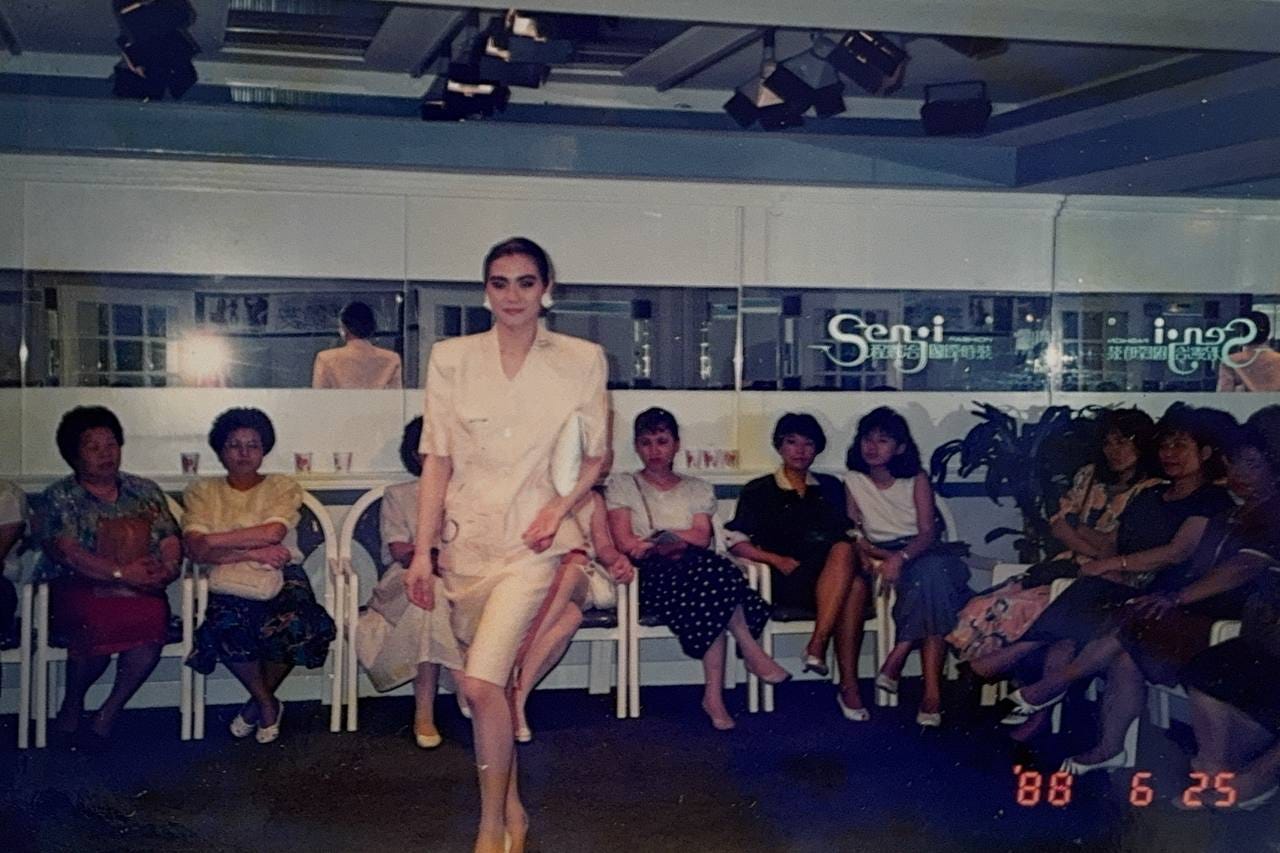

I enjoy listening to my mother talk about her younger self: rebellious, difficult, but most of all, courageous. The years have narrowed her appetite for risk. She calls most new things “a hassle,” which I’ve learned is just fear. I sometimes wonder if I will also grow more fearful when I get older. Part of why I left Tokyo was so I could fly back to Asia with her; she wouldn’t have gone alone. My hope isn’t reinvention. It’s remembrance. That she might recover the feeling that life is still open, that curiosity doesn’t expire just because responsibility arrived first. That she might remember that life, though fast, is still wide.

There are quieter moments, though, when something less flattering surfaces. Resentment. I’ve spent years thinking about filial piety, not to reject it, but to understand it.

After nearly four years of working with my coach, I know my deepest grief comes from what’s politely called a “parent wound.” Friends remind me that it isn’t a child’s job to save their parent. I understand that, intellectually. Still, I watched her give herself away repeatedly—first as a daughter, then a wife, then as my mother. My ache is not that she struggled, but that she never lived as a woman unclaimed by obligation.

I grew up between two moral architectures. One insists that adulthood means autonomy, clear boundaries, and self-actualization. The other teaches that love is endurance, that duty is a form of devotion, that you carry your parents not because you must, but because you can. Most days, I translate fluently between the two. Other days, I feel stranded, suspended between languages that ask different things of me. Filial piety can feel like a cage when it crowds out my own becoming. It can also feel like an honor, heavy and gleaming, when I remember what was given so I could stand where I am. I am not confused about which world I belong to; I’m simply aware that I belong to both, and that belonging is rarely weightless.

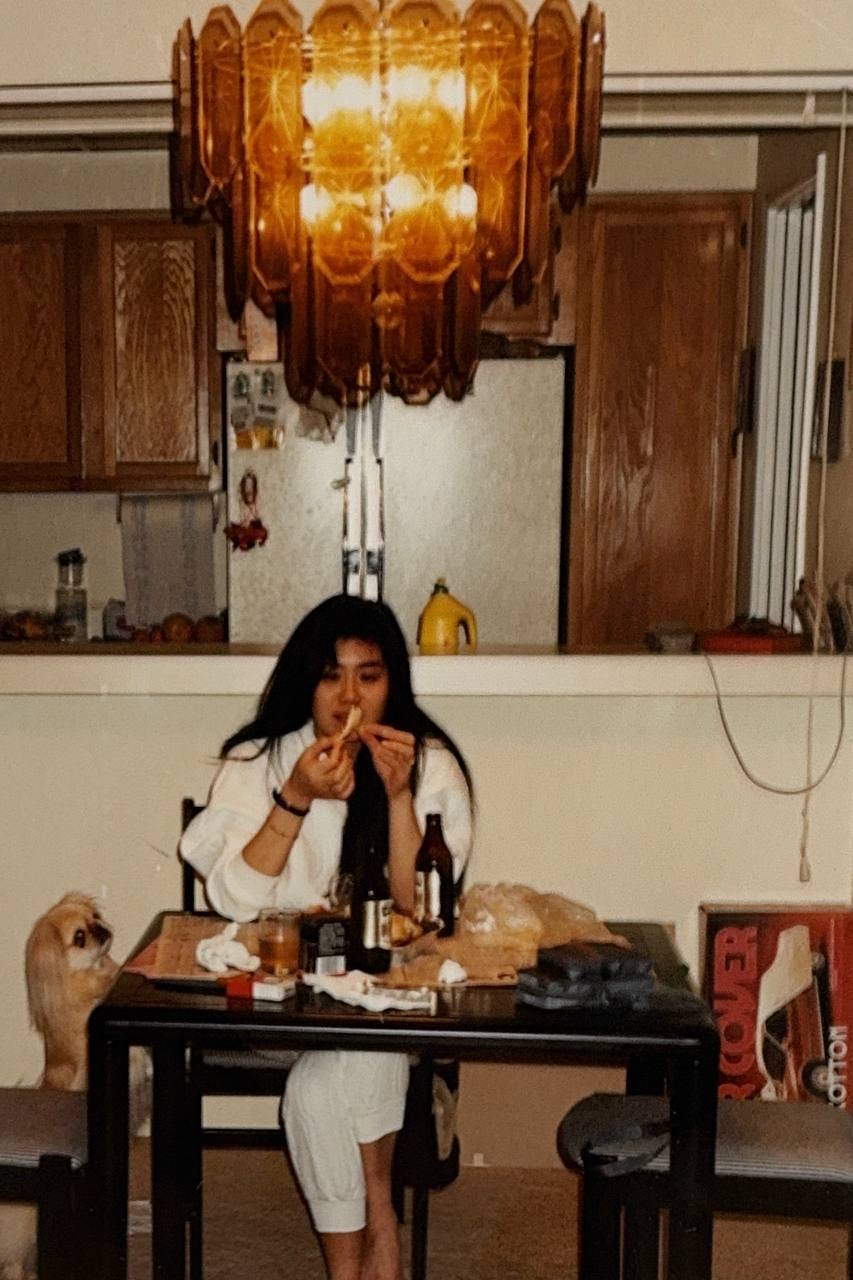

At home, this tension shows up in small, domestic ways. The way I remind her to take more walks, then resent myself for sounding like a parent. The way I watch her push healthy food around her plate while insisting she’s full, and quietly wrap the leftovers anyway. The shared silence while we run errands around the house, each of us pretending not to notice the other’s fatigue. I memorize her routines the way some people memorize prayers: how she double-checks the stove, how she saves plastic bags, how she still cuts fruit for me even though I’ve spent a decade living on my own before. These are not grand sacrifices. They are intimate ones. And in these moments, over tea gone cold, over suitcases half-packed, over evenings that don’t need to be filled with conversation, I understand why my life looks the way it does from the outside.

So when people ask why I don’t prioritize settling down, why I work so much, why I’m rarely out with friends, I struggle to give them an answer that doesn’t sound defensive or self-important. The truth is simpler, yet heavier. I have goals, yes, but not the kind that end in applause. I want time to slow in ways it rarely does. I want to afford her wonder. I want to make sure she gets to live, at least a little, untethered.

Loved the choice of words in describing your “navigating between two moral architectures.” Such an elegant articulation yet so rich in meaning.

💕